Letters of Intent - Every Deal has a "Feel"

After a lengthy absence, we're back on the grind and working to resume our semi-monthly publishing schedule. Welcome to our new readers and thanks to our returning ones!

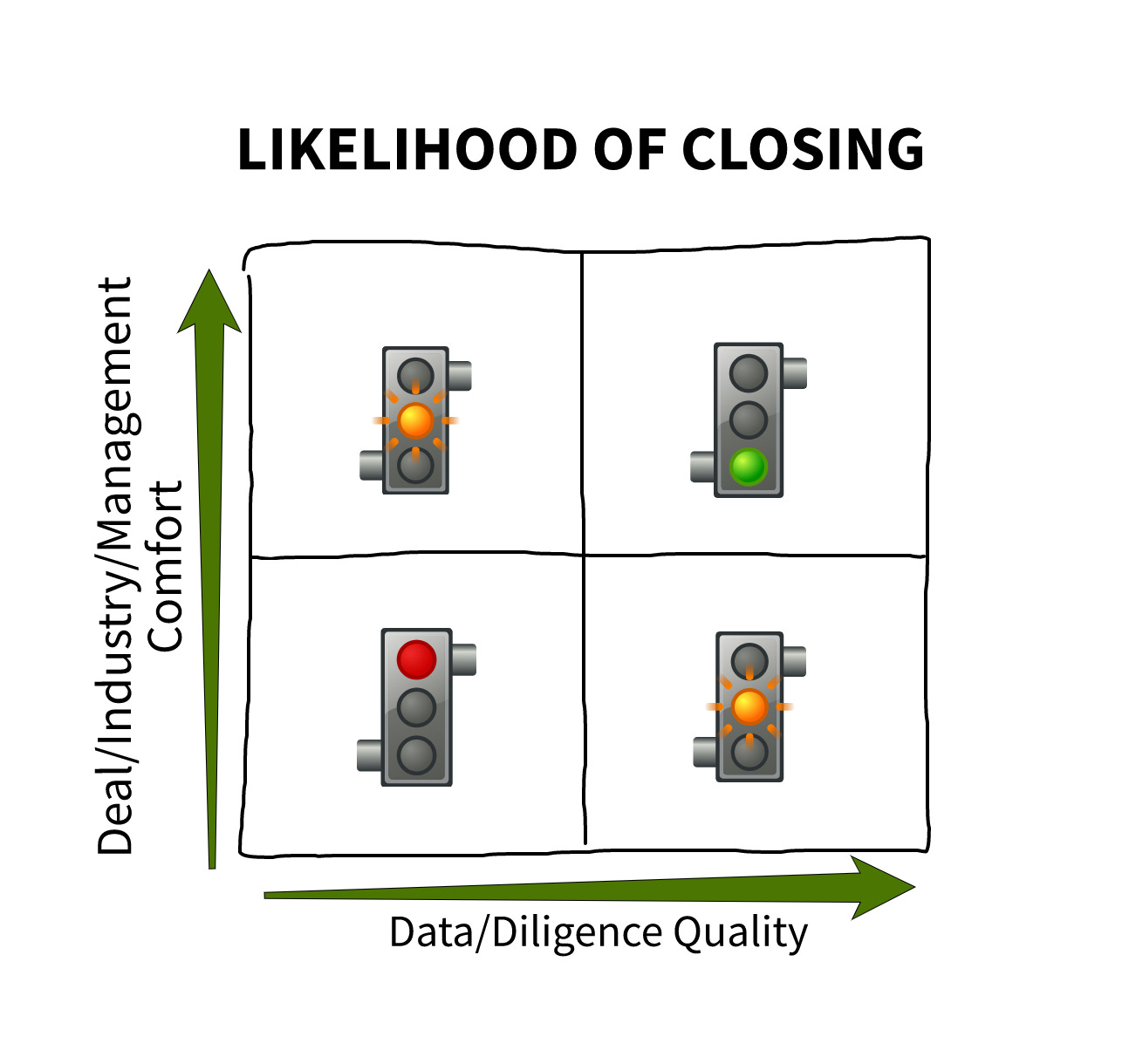

Every experienced buyer dreams of the day when a deal will sail smoothly from first contact to closing with no headwinds or choppiness. That seldom (ever?) happens in practice. This note explores a more general sense, gained through experience, that I’ve noticed after reviewing and pursuing a large number of deals. It is an emergent feeling that grows or subsides as evidence and data is gathered, but which often is indicative of the ultimate outcome of a potential transaction. Ultimately, it translates into a gut sense of how likely a deal is to make it across the finish line and is comprised of both ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ data points (on a 2x2 matrix, this might have axes of ‘deal/industry/management comfort’ and ‘data/diligence quality’). Most deal professionals will, I think, be able to identify with what I describe below, but may never have given explicit thought to it as a more general framework for their work.

The Softer Elements of a Deal

Each company available to a buyer requires a lot of investigation and analysis as part of the underwriting. Legal, tax, accounting, market, insurance, etc. Most of this results in a lot of data about the company being collected which can be objectively evaluated. Is there customer concentration? What insurance policies are carried and are they sufficient in their coverage? Is the company growing? Is employee turnover high?

There are also softer elements in a deal: does the seller seem trustworthy, do customers and staff appear to be treated with respect, is the office or facility clean and organized, are messages returned promptly and questions answered directly, etc. A lot of the assessment for those items is subjective. That makes it easier, mentally, to discount or ignore troublesome thoughts and findings that are encountered. But that’s risky. In small business acquisitions, it is often the case that you’re buying from the founder of the company; that person’s DNA runs deep and the company frequently exhibits many of the same cultural and behavioral traits as its leader, so I’d urge extreme caution when factors in this category of diligence aren’t throwing off strong and positive signals. The rub, unfortunately, is that developing the judgment to perceive what’s important and what isn’t in these areas takes time and practice (and, usually, mistakes).

The “Feel” of a Deal

With enough practice, however, generated by thoughtfully and diligently reviewing hundreds of opportunities, a buyer starts to develop an instinctual feeling about each opportunity, one that blends both the hard and soft aspects of the deal. Very quickly, a judgment (still malleable, but often correct) is made as to the prospects of success in completing the acquisition. Sometimes this feeling can emerge as early as during the first call with an owner or the first pass through an intermediary’s materials on a company. A buyer can look for ‘tells’, such as: Is bad news communicated proactively? Does the seller speak more in terms of the company and team or themselves when highlighting accomplishments? Are investments being made into the team (training, equipment, etc.) to support their own personal as well as the company’s objectives?

When this feeling arises and feels positive, it is as if the normal cobbled streets of deal-making have just been resurfaced with new, smooth asphalt. When the feeling is bad, those small cobbles start to take on the appearance of large boulders. And, if this sixth-sense doesn’t materialize until later in the process, perhaps well after an LOI has been signed, that’s also often an indicator of how likely it is that a deal will make it to a successful closing.

Personally speaking, when my feelings about the integrity and responsiveness of a seller or the company’s quality of operations and culture trend in a positive direction, unless something material changes in the business, my confidence grows that any smaller obstructions during negotiations will be cleared; similarly, when stories aren’t making sense and information is slow to be produced, or only partially provided with no explanation, my sense of the odds that the purchase will take place decline quickly. This can turn what initially felt like a strong opportunity into one to avoid. Backing out for a feeling, largely based on subjective criteria, is emotionally hard, especially when it happens in the more advanced stages of a closing process. But, it is always better to avoid buying a potentially bad company than it is to convince yourself that what you’re seeing and feeling isn’t real.

The 2x2 Matrix: Some Final Thoughts

In the matrix above, there are four possible situations in which a buyer can find themselves. The best case is where both the objective facts are strong and reinforce the investment thesis and the softer, subjective judgments also tilt highly positive. In these cases, conviction about the investment’s prospects are high and investors will often lean into these processes and work in earnest to complete the acquisition. Conversely, in situations where both factors are low or negative, investors are likely to abandon their pursuit of the business. In cases where the due diligence findings and facts are good, but where the buyer’s intuition or comfort with the other aspects of the deal are lower or the reverse (bad diligence facts, but strong levels of subjective comfort), the buyer should proceed with caution — and in almost all of those situations — pass on the opportunity.

Why draw a hard line in those situations? In a case where the fundamental data is poor, but the founder and company dynamic is good, it should be relatively easy to develop a conclusion to pass simply by conducting an objective assessment of the facts. In the opposite case, where the objective diligence findings are strong, but the comfort factors are weak, it can be harder to pass as investors can more easily convince themselves that either their judgment on those factors is off (harder to verify since everything is subjective) or that the issues can be resolved in due course after the closing since the fundamentals appear to be strong.

As someone who has made — and will inevitably continue to make — mistakes in this evaluation process and in situations exemplified by both of the mixed quadrants (high/low, low/high), I think the best response is to be as disciplined as possible about making the subjective objective, largely by developing checklists and processes that document the favorable and unfavorable characteristics that contribute to the subjective diligence elements of any deal. The ultimate goal, though elusive, is to ONLY do deals in the upper right quadrant.

One last consideration: for investment firms building teams and trying to create enduring franchises, this combination of hard and soft diligence assessment is at the very core of great investment decision making. Taking the principals’ judgment and codifying it in such a way that other investment professionals can benefit from the experience and wisdom of the partners is essential. It shortens the learning curve for those professionals and helps to increase scalability of the team’s ability to transact. As an apprenticeship model, distilling the hard-earned experience and judgment of the more senior team members in a manner that provides functional and clear guidance and guardrails on every aspect of diligence is extremely helpful in streamlining the diligence workflow and reducing variance in investment outcomes.

How do you assess the subjective areas of a potential acquisition and integrate them into an overall ‘feel’ for your deals? Leave a comment by clicking below.

HoldCo Survey

Friends of the firm, John Wilson and Kelcey Lehrich, operators themselves, but also founders of HoldCoConf, a holding company conference, have developed a survey on that topic and are looking for respondents. If you operate a holding company, or know someone who does, they would be appreciate if you completed or shared the survey, as appropriate.

Click here for the survey.